This is the first year that I’ve participated in Ada Lovelace Day, and I decided to pick a woman from history, related to my own field and who I’d not heard of previously, so that I’d have to do some research. I came across the plant anatomist and later electron microscopist, Katherine Esau.

Katherine Esau

Katherine Esau working at the electron microscope – Copyright Cheadle Center for Biodiversity and Ecological Restoration

Katherine Esau was born in the city Yekaterinoslav, in the then Russian Empire (now Dnipropetrovsk, Ukraine) in 1898. It was in Russia that she received her early education, until 1917, when the Russian revolution and later German occupation of Ukraine prevented her from completing her studies at the Golitsin Women’s Agricultural College, Moscow.

Esau and her family fled to Germany, moving to Berlin. Here, she was able to continue her studies by enrolling at the Berlin Landwirtschaftliche Hochschule (Agricultural College), completing them in 1922.

Later in 1922, the Esau family moved again, this time to California, USA. It is here that Esau made home for the rest of her life. After some short term jobs, her research career began in earnest with a job at Spreckels Sugar Company. Her project was to develop a sugar beet resistant to curly top disease, a virus carried by beet leafhoppers. This research led to her gaining a position doing similar research as a graduate student at UC Davis in 1927.

Unfortunately (or perhaps fortunately, given Esau’s later success), this project turned out not to be viable at UC Davis, and Esau’s attention was turned to plant anatomy and the effect of the curly top virus on the plant. For this research she was awarded a PhD in 1931.

Esau stayed within the University of California for the rest of her career, first at Davis and later at Santa Barbara, and continued researching the same themes; plant anatomy and virus-plant interactions. In particular, Esau studied the phloem, the tissue that distributes nutrients throughout plants and how viruses such as curly top use this to spread, as well as studying healthy plant anatomy.

My interest in Esau comes from her later work, setting up an electron microscopy laboratory and using this technique to study virus-diseased plants. These are techniques not a million miles away from those I use to look at cells today. Much of this work was carried out after Esau retired, as despite retiring in 1965, she continued to work for many more years, including supervising PhD students.

In addition to her research and teaching, Esau also wrote and illustrated two key textbooks in plant anatomy; “Esau’s Plant Anatomy” and “Anatomy of Seed Plants”, both of which continue to be on university reading lists today, amongst many other books and publications.

During her career, Esau picked up many awards for her work, including the National Medal of Science in 1989, Certificate of Merit from the Botanical Society of America in 1956, and election to the National Academy of Sciences in 1957. She became only the sixth woman to be elected to the Academy. She was also president of the Botanical Society of America and now gives her name to one of their awards, the Katherine Esau Award, given to “the graduate student who presents the outstanding paper in developmental and structural botany” at their annual meeting. UC Davis also runs a post-doctoral fellowship in her name.

As part of her autobiography and oral history in 1991, David Russell asked her about women in science and her experience:

When I first arrived in the United States, many people expected me to do just ordinary things, housework and getting married and so forth—the same routine. But I was more ambitious.

and

I never worried about being a woman. It never occurred to me that that was an important thing. I always thought that women could do just as well as men. Of course, the majority of women are not trained to think that way. They are trained to be homemakers. And I was not a homemaker.

However, on promotion and her former boss, Esau says;

I now learn from people that he actually did not like to have a woman in the department. He did not treat me right, but I didn‘t notice it. I thought that was the way it was done. I never even questioned it. For example, he was very reluctant to give promotions. Nowadays they often jump one step, and people just go right through the appointments very quickly. But at that time, we went six years in each grade. Six years. It never changed. But then when a new director arrived on the campus, he looked at my record and said that I was not getting enough salary. So he raised my salary, but our chairman, Dr. Robbins, would not do it.

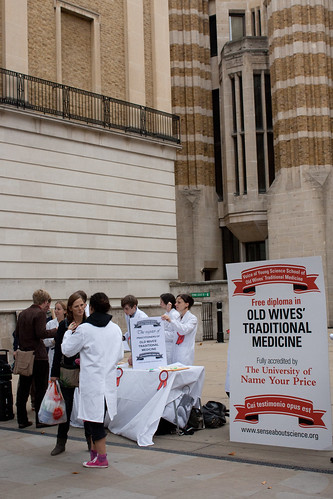

About Ada Lovelace Day

Ada Lovelace (1815-1852) is known as the world’s first computer programmer for her work with Charles Babbage on his Analytical Engine. She gives her name to a Ada Lovelace Day, in mid-October each year where we “celebrate the achievements of women in science, technology, engineering and maths” (STEM). The day is generally marked by people creating and sharing blogposts, videos and other material about an inspiring woman in STEM.