We are bombarded with ‘expert opinions’ every day in the media, both printed and broadcast, and many of these people are presented to us with their title: Prof, Dr, PhD, FRS and the like. An example might be this recent story on sleep deprivation and stroke from the Guardian, which is followed throughout.

My questions are: does including their “rank” in the scientific hierarchy automatically say to the audience “you should believe this person for they are more qualified than you“, is this committing an ‘argument from authority‘ and does this even matter at all?

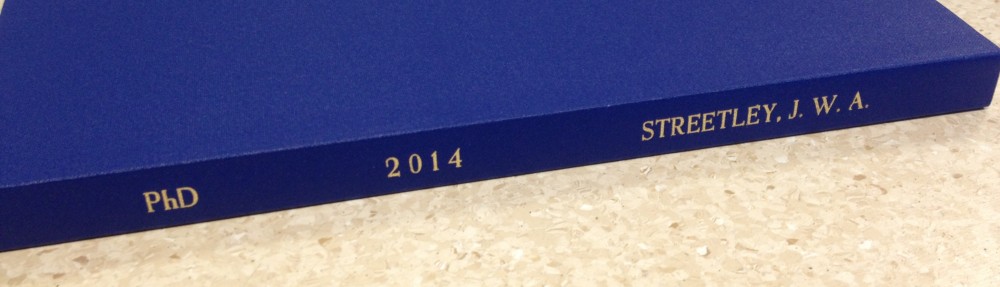

The first question translates basically to whether or not an academic’s title is optional. On the one hand, they’ve earned the degree/accolade by working pretty damn hard and deserve to be called by it. In 3 years time, when (hopefully) I finish my PhD, I’ll be pretty cheesed off if ‘Dr’ doesn’t get written down in the right places. On the other hand, within science (certainly biology/biochemistry), people don’t much use their titles. At the institute where I work, titles are basically relegated to the telephone directory and a handful of email signatures. They certainly don’t appear on published papers, so why in the press release and press coverage. (As an aside, this is different in the medical world such as the BMJ, The Lancet and NEJM, where author qualifications are published). If they aren’t on the paper itself, I think that says to me that they aren’t needed in the press coverage, but I’ll admit that it’s an open question.

Does the inclusion of these titles confer authority on to whatever quote their holder is giving? I think they probably do. This might not be the intention in science reporting but it has that effect. Why else would people be so keen to use the title Dr, if not to be accepted as an expert in a field?

A better question is whether worrying about presenting a well-qualified expert as an authority figure actually matters? As noble as the Royal Society’s motto might be (nullius in verba – On the word of no-one), equally nobody has time to fact check everything, and qualifications and titles are often a pretty good heuristic for reliability. As Paul Nurse (or perhaps “the Nobel laureate Sir Paul Nurse PRS) recently put to James Delingpole (3m30s), when you go to a doctor, you trust their clinical judgment. You might do your own research and disagree with the consensual position, but that would be a very unusual position to take.

The problem – as there is with all such rules of thumb – is that it is open for exploitation. I alluded earlier to those who ‘pass off’ having more qualifications than they have, often in order to lend their opinion legitimacy, often for monetary gain in the form an endorsement by an expert. Weirdly, this means that every time a title such as Dr is used legitimately, it adds weight to all those using the same title illegitimately. A reverse problem can also occur – someone with a legitimate qualification, in a relevant field presents a maverick view rather than scientific consensus and can be spectacularly wrong, but still taken “on authority”. Think Andrew Wakefield and the disproven MMR/Autism link for an example.

On balance, I’m not sure that there is a right answer to the use of academic titles. To me they are a mark of respect and achievement, not authority and certainly don’t mean that everything the holder says is true and sacrosanct, but I’m not sure that is always how they are taken.

“James Streetley BSc (Hons) MRes“